Introduction

Some time ago, I noticed that Dallas County, Iowa had the greatest increase of any large county in the country in percentage of residents 25 years and older having at least a bachelor's degree.

I use "large county", incidentally, in the sense of being one of the 814 counties with an ACS 1-year estimate (although the Census tract maps use 5-year estimates), but these cover about 84% of the U.S. population.

Dallas County--a suburban and rural county immediately west of Polk County (Des Moines) which holds the rare distinction of voting Mondale/McCain, as Pete Helgason pointed out to me--went from having 26.8% of residents with at least a bachelor's degree to 42.6% (1-year estimate) or 42.1% (5-year estimate)--either way, an increase of more than 15 points.

(Thanks to BikeIowa for that map.)

That's higher than the District of Columbia (second on the list, +13.9% from 39.1% to 53%). I decided I wanted a more granular look at this remarkable demographic shift. But long story short? Make sure you map change in total population.

Note: When I say 2012, below, take it to mean "from 2012 5-year estimates". There's also a GitHub pages version of this post, so you can see the source for the maps and so on, here.

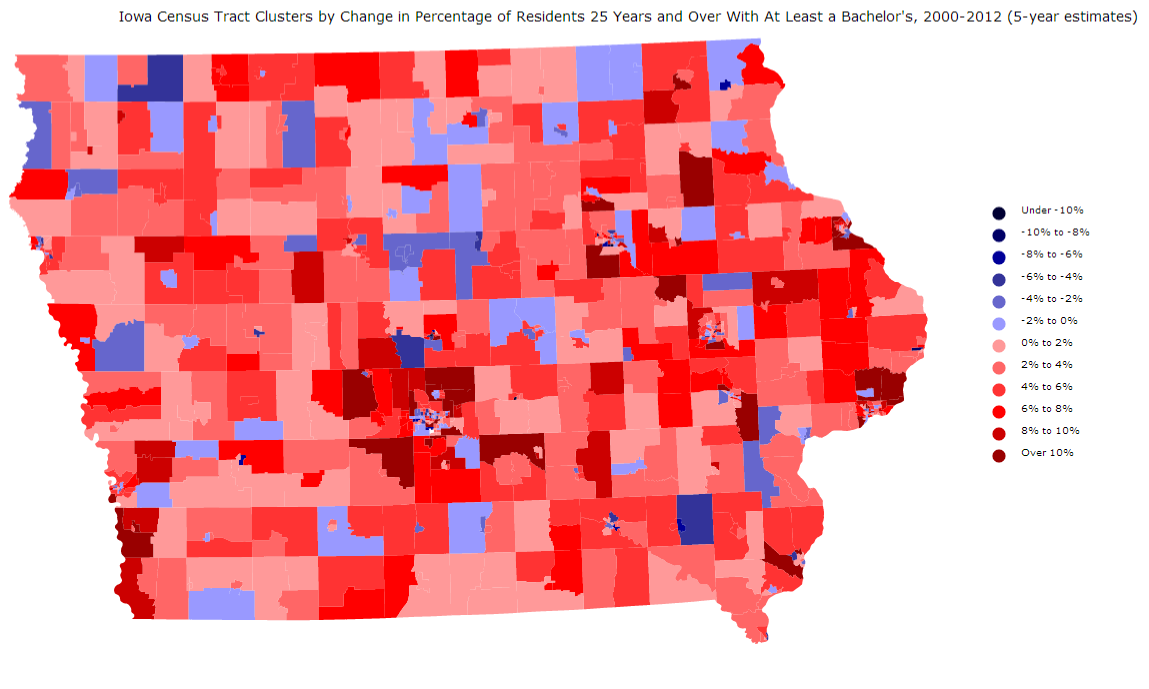

First Map: Change Within Tracts

My first approach was the same as the one I used in my "Where Has New York City Changed In The Last 10 Years" post: I combined 2000 and 2010 Census tracts into comparable clusters using Census tract relationship files, and made a map similar to the following. Red tract clusters had increases in percent with a bachelor's degree, blue tract clusters had decreases:

Unfortunately, Dallas County doesn't particularly stand out here. Its tract clusters mostly increased their percentage of degree holders, but no single tract cluster had an increase as large as the county as a whole.

How was that possible? I checked the math by hand, and it wasn't a typo--so the above map isn't explaining what's going on.

Second Map: Change in Total Population

It took me a little while to realize that the answer wasn't in the change within tracts, but in the change between them.

Here is a map of tract clusters, colored by change in total population. Again, red means increase, and blue means decrease.

Now, Dallas County stands out--actually, it's not all of Dallas County standing out, but that single cluster of six Census tracts in the southeast. As you can see in the first map or in the below Google Maps screenshot, this cluster includes parts of communities like Clive, Urbandale, Waukee, and West Des Moines, many of which literally sprawl over from Polk County.

This cluster had enormous growth from 2000 to 2012. The population more than tripled (from 10,139 people to 34,332) as did the population over 25.

In fact, it had the second-highest growth rate of any tract cluster in the entire state, behind only a tract covering outer Akney, in Polk County. Without it, Dallas County would have had barely any growth at all. The cluster went from being less than one-fourth of the county to being about half of it. The reapportioning commission basically had to draw an entire new state legislative district to cover this area (House District 44).

Explanations

What does this have to do with education? This same cluster is also the most educated part of the county. In 2012, 59.2% of the cluster's residents over 25 had at least a bachelor's degree, compared to 24.1% of the rest of the county:

In 2000, 52.9% of the cluster's residents over 25 had at least a bachelor's degree, compared to 18.4% of the rest of the county:

In other words: The county as a whole had a 15-point increase, but inside this particular cluster there was roughly a 6-point increase, and outside the cluster there was roughly a 6-point increase. Everything else is from change in population size.

Conclusion

Dallas County, Iowa had notable demographic change from 2000 to 2010, with its proportion of residents with a bachelor's degree increasing by 15 points.

However, most of this change wasn't due to the change in any particular neighborhood (at least any particular neighborhood bounded by Census tracts). Rather, much of the change was due to the explosive growth in the most educated part of the county compared to the remainder.

This is kind of a variant of Simpson's paradox, and I think it's an important lesson for map-makers: Look at the change in population between regions, and not simply the changes within regions. Otherwise, you might miss a lot of what's going on.

Also: If Dallas County had been divided into two counties--one for the rural part, one for the cluster of urban sprawl--and the area developed the same way, then no county would have had a 15% increase in residents over 25 with at least a bachelor's degree. (Instead, one county would have tripled in population--so something notable did happen.) So that showy 15% increase is, in some ways, an artifact of the (arbitrary) county lines. We should think about similar possibilities when looking at any demographic fact or shift.

Data Sources

Numbers from 2000 are from the Census, and numbers from 2012 are from the ACS 5-year estimates.

I used Census tract relationship files, a Python script and the "union-find" method to combine the tracts into comparable "clusters" after throwing out polygons with no current population.

All of the above data sources can be found here. I was also helped by various Mike Bostock blocks, such as this one, etc.

Xenocrypt's Site.

Political history, math, you know--trendy stuff.

Wednesday, May 21, 2014

Monday, September 23, 2013

Mapping Historical Votes: Prohibition Passes The House.

Introduction:

In a previous post, I mapped when women's suffrage failed in the U.S. House in 1915. For this post, I thought I'd map the (House) passage of the Eighteenth Amendment: Prohibition.

Here's a link to the vote on Govtrack. The prohibition amendment was sent to the states by a vote of 282 to 128--a landslide in absolute terms, but relatively close given the margin required to pass a Constitutional amendment.

The 65th House of Representatives was closely divided between Republicans and Democrats. 208 Democrats, 201 Republicans (one "independent"), 3 Progressives, 1 Socialist, and 1 Prohibitionist voted on the Eighteenth Amendment.

Remarkably enough, the major parties split in nearly identical ratios on this issue, with 140 Democrats and 138 Republicans supporting Prohibition, and 64 Democrats and 62 Republicans in opposition. Even the 3 Progressives followed the pattern and split 2-1.

I also used green for the sole Prohibitionist, outer Los Angeles County's Charles Randall, and purple or something for the sole Socialist, Meyer London, who represented an astonishingly tiny slice of the Lower East Side of Manhattan. London voted "Nay", and you can probably guess how the Prohibitionist voted on Prohibition.

One immediately useful comparison is this map from an Anti-Saloon League book showing which parts of the country had already gone "dry" by March of 1917, before the vote on the Eighteenth Amendment:

Let's take a closer look at a few regions.

The Cities:

Again following Martis' maps, I've added insets for urban areas. This is particularly useful here, because we can easily see the extent to which Prohibition was a "city-country" vote.

Of the Representatives of the very largest cities, only a very few backed Prohibition:

-The sole New York City Congressman to support Prohibition was Brooklyn Republican Frederick Rowe, whose district included Borough Park. Go figure. NY-14 has no vote listed, but it was represented by a notoriously anti-Prohibition Republican: Fiorello La Guardia, who was presumably over in Italy on his WWI missions.

-The Anti-Saloon league listed IL-10 Republican George E. Foss as a resident of Chicago, and he voted for Prohibition. A 1912 article in Collier's Magazine describes the district as "Lake County and four precincts of the city of Chicago", but Lake County wasn't very big in 1917.

-The four central Philadelphia districts opposed Prohibition, but two peripheral Philadelphia Representatives, Peter Costello and George Darrow, supported the amendment.

-Pittsburgh-area Progressive Melville Kelly supported Prohibition as well, although I'm not sure how much of Pittsburgh proper he represented. The Anti-Saloon League has him as a resident of Braddock, Pennsylvania.

-Although Los Angeles would soon be named one of the 10 largest cities in the country by the Census, its delegation (downtown Republican Henry Osborne and the aforementioned Prohibitionist Randall) unanimously backed the Eighteenth.

-Minneapolis Congressman, and future Senator, Ernest Lundeen supported Prohibition, even though Minneapolis' Hennepin County had remained "wet" under the local option (although the Anti-Saloon League claimed fraud).

Past that, Prohibition supporters are a bit easier to find: Indianapolis, Rochester, Denver, Columbus, and Oakland districts supported Prohibition, although Jersey City, Portland, Toledo, Providence, Louisville, and St. Paul districts opposed it. (For some reason none of the Boston Representatives have a vote listed, nor does Seattle's WA-01. I'm not sure which Rhode Island districts included which parts of Providence proper.)

The South:

Will Rogers famously said "The South will vote dry, at least as many as can stagger to the polls". Or at least I've seen versions of that quote attributed to him. Much of the South had already enacted statewide Prohibition, as the above map shows. But I was more intrigued by how many Southerners voted against the Eighteenth Amendment, although the region was still strongly in favor of Prohibition overall.

Many of the "wet" Southern districts were on the Gulf Coast, including all of coastal Louisiana, most of coastal Texas, and a bit of Alabama. Southern Louisiana had remained "wet" under the local option. (One notable Texan who voted against Prohibition was future Vice-President John Nance Garner, who was apparently pretty open in his defiance of the law.)

It's particularly interesting how many Alabama Representatives voted against Prohibition, since the state had already voted "dry". In fact, 5 of Alabama's 10 Representatives voted against the Amendment, from the coast to Birmingham.

Oddly, the Encyclopedia of Albama describes one of these "No" votes, Birmingham's George Huddleston, as a "champion of...Prohibition". But Huddleston himself said "I believe in Prohibition, but I can not vote to force it on communities remote from my own, of which I have no specific knowledge and in which I have no particular interest". J. Thomas Heflin bragged that his district was already "dry as a covered bridge" (in fact, earlier than the rest of the state) and that this was precisely why he opposed the federal amendment. On the day of the vote, TX-14 Democrat James Slayden proclaimed Prohibition "the overturning and revolutionizing of the Federal Union and the destruction of the States".

Of course, it's hard to separate genuine libertarian inclinations with the darker reasons some Southerners might have feared a bill increasing the power of the Federal government.

North Carolina Democrat Edward Pou probably made the implicit fears of some of his colleagues explicit when he warned that if a Prohibition amendment could pass, then so might an amendment "to prescribe the qualification of voters in all the...states of the union".

Aside from Pou, South Carolina's Frederick Dominick and North Carolina's John Small also opposed the Eighteenth. So did three Kentuckians: Arthur Rouse, James Cantrill, and Joseph Sherley. I imagine alcohol was a larger part of the culture and economy of Kentucky than in other Southern and border states (after seeing the map, a friend pointed out that one of their districts included Bourbon County). Their districts were also relatively urbanized: Sherley represented Louisville, Cantrill's district included Lexington, and Rouse's district was adjacent to Cincinnati and its significant German-American population (see below).

If I remember V.O. Key's "Southern Politics" correctly, the divide in Southern states over "moral issues" was often between their more urban, coastal, and commercial areas (which tended to support laxer policies and often had larger African-American percentages) and their whiter, more rural areas (which tended to support more restrictive policies).

The divisions in Alabama and Louisiana might fit that pattern here, although they only cover some of Alabama's "black belt". Interestingly, the specific example that I remember from Key is Mississippi, whose House delegation was unanimously "dry".

German-American Regions:

I've read historians who point out connections between the Prohibition movement and nativism--alcohol being a larger part of the cultures and even religious ceremonies of Irish, Italian, and German immigrants than of the (official) culture of "old stock" Protestants and so forth. And of course, urban "machines" surely liked their taverns and saloons, although I'm sure many of them learned to love Prohibition even more.

Here is Wikipedia on where German-Americans were concentrated. Compare with the vote map:

To back that up, here is a Stanford visualization of German-language newspapers in 1917:

And here is a lovely map of the German-American population of about 1872 from that Wikipedia page:

There isn't a perfect correspondence, but there's enough to be interesting. Along with some of the big cities we've already discussed, the eastern border of Wisconsin (up from Milwaukee), the Western border of Ohio (up from Cincinnati), the St. Louis area, Northern Kentucky, Erie, Pennsylvania--all seem to have had high percentages of German-Americans, and all had Representatives voting against Prohibition. (The votes in Rhode Island's three districts seem to match pretty well with the 1872 map.)

The sole Iowa vote against Prohibition came from Harry Hull, whose district included Davenport's Scott county, and who succeeded another anti-Prohibition Congressman, the former Davenport Mayor and "archetypal German-American politician" Henry Vollmer.

However, there are exceptions: Omaha was heavily German-American, and the Representative of the Omaha district, Charles Lobeck, was himself German-American. Lobeck voted for the Eighteenth anyway. The entire Indiana delegation voted for Prohibition as well.

The West:

Representatives from the West voted heavily "dry", and much of the West was dry before the vote on the Eighteenth. California wasn't dry, but did have this depressing law:

Only a few Western Representatives opposed the Eighteenth amendment, including three urbanites (Portland's Clifton McArthur and the San Francisco Republicans Julius Kahn and John Nolan).

California Democrat Clarence Lea had a sound parochial reason for his vote against total Prohibition: He represented California's wine country. In fact, citing "conditions that affect my district", he proposed an amendment on the day of the vote "exempting light wines and beers containing not more than 3 per cent. of alcohol".

The other Westerners opposing Prohibition were the Central Valley Democrat, Denver Church, and Nevada's Edwin Roberts. (Nevada remained mostly "wet" before the vote.) Roberts was eventually elected the Mayor of Reno, where he remained defiantly anti-Prohibition, once claiming in a speech "that the only way to deal with bootlegging was to 'place a barrel of whiskey with a dipper in it on every corner.'"

One notable Westerner voting for the Eighteenth was Montana At-Large Republican Jeannette Rankin. (Montana also had an At-Large Democrat voting "dry", John Evans, but I decided to map Rankin for her historical importance.)

In a previous post, I mapped when women's suffrage failed in the U.S. House in 1915. For this post, I thought I'd map the (House) passage of the Eighteenth Amendment: Prohibition.

Here's a link to the vote on Govtrack. The prohibition amendment was sent to the states by a vote of 282 to 128--a landslide in absolute terms, but relatively close given the margin required to pass a Constitutional amendment.

The 65th House of Representatives was closely divided between Republicans and Democrats. 208 Democrats, 201 Republicans (one "independent"), 3 Progressives, 1 Socialist, and 1 Prohibitionist voted on the Eighteenth Amendment.

Remarkably enough, the major parties split in nearly identical ratios on this issue, with 140 Democrats and 138 Republicans supporting Prohibition, and 64 Democrats and 62 Republicans in opposition. Even the 3 Progressives followed the pattern and split 2-1.

The Map:

Here's the map. Once again, I used the historical Congressional shapefiles (by Jeffrey B. Lewis, Brandon Devine, Lincoln Pritcher, and Kenneth Martis), along with Govtrack.

Here's the map. Once again, I used the historical Congressional shapefiles (by Jeffrey B. Lewis, Brandon Devine, Lincoln Pritcher, and Kenneth Martis), along with Govtrack.

I colored by party as you'd expect (red is Republican, blue is Democratic), with yellow for Progressives. The darkest color means a vote of "aye", the second-darkest color means a vote of "nay", and the third-darkest color means a vote was recorded as missing or wasn't recorded at all, or there was a vacancy in a district that didn't change parties.

I also used green for the sole Prohibitionist, outer Los Angeles County's Charles Randall, and purple or something for the sole Socialist, Meyer London, who represented an astonishingly tiny slice of the Lower East Side of Manhattan. London voted "Nay", and you can probably guess how the Prohibitionist voted on Prohibition.

One immediately useful comparison is this map from an Anti-Saloon League book showing which parts of the country had already gone "dry" by March of 1917, before the vote on the Eighteenth Amendment:

Let's take a closer look at a few regions.

The Cities:

Again following Martis' maps, I've added insets for urban areas. This is particularly useful here, because we can easily see the extent to which Prohibition was a "city-country" vote.

Of the Representatives of the very largest cities, only a very few backed Prohibition:

-The sole New York City Congressman to support Prohibition was Brooklyn Republican Frederick Rowe, whose district included Borough Park. Go figure. NY-14 has no vote listed, but it was represented by a notoriously anti-Prohibition Republican: Fiorello La Guardia, who was presumably over in Italy on his WWI missions.

-The Anti-Saloon league listed IL-10 Republican George E. Foss as a resident of Chicago, and he voted for Prohibition. A 1912 article in Collier's Magazine describes the district as "Lake County and four precincts of the city of Chicago", but Lake County wasn't very big in 1917.

-The four central Philadelphia districts opposed Prohibition, but two peripheral Philadelphia Representatives, Peter Costello and George Darrow, supported the amendment.

-Pittsburgh-area Progressive Melville Kelly supported Prohibition as well, although I'm not sure how much of Pittsburgh proper he represented. The Anti-Saloon League has him as a resident of Braddock, Pennsylvania.

-Although Los Angeles would soon be named one of the 10 largest cities in the country by the Census, its delegation (downtown Republican Henry Osborne and the aforementioned Prohibitionist Randall) unanimously backed the Eighteenth.

-Minneapolis Congressman, and future Senator, Ernest Lundeen supported Prohibition, even though Minneapolis' Hennepin County had remained "wet" under the local option (although the Anti-Saloon League claimed fraud).

Past that, Prohibition supporters are a bit easier to find: Indianapolis, Rochester, Denver, Columbus, and Oakland districts supported Prohibition, although Jersey City, Portland, Toledo, Providence, Louisville, and St. Paul districts opposed it. (For some reason none of the Boston Representatives have a vote listed, nor does Seattle's WA-01. I'm not sure which Rhode Island districts included which parts of Providence proper.)

The South:

Will Rogers famously said "The South will vote dry, at least as many as can stagger to the polls". Or at least I've seen versions of that quote attributed to him. Much of the South had already enacted statewide Prohibition, as the above map shows. But I was more intrigued by how many Southerners voted against the Eighteenth Amendment, although the region was still strongly in favor of Prohibition overall.

Many of the "wet" Southern districts were on the Gulf Coast, including all of coastal Louisiana, most of coastal Texas, and a bit of Alabama. Southern Louisiana had remained "wet" under the local option. (One notable Texan who voted against Prohibition was future Vice-President John Nance Garner, who was apparently pretty open in his defiance of the law.)

It's particularly interesting how many Alabama Representatives voted against Prohibition, since the state had already voted "dry". In fact, 5 of Alabama's 10 Representatives voted against the Amendment, from the coast to Birmingham.

Oddly, the Encyclopedia of Albama describes one of these "No" votes, Birmingham's George Huddleston, as a "champion of...Prohibition". But Huddleston himself said "I believe in Prohibition, but I can not vote to force it on communities remote from my own, of which I have no specific knowledge and in which I have no particular interest". J. Thomas Heflin bragged that his district was already "dry as a covered bridge" (in fact, earlier than the rest of the state) and that this was precisely why he opposed the federal amendment. On the day of the vote, TX-14 Democrat James Slayden proclaimed Prohibition "the overturning and revolutionizing of the Federal Union and the destruction of the States".

Of course, it's hard to separate genuine libertarian inclinations with the darker reasons some Southerners might have feared a bill increasing the power of the Federal government.

North Carolina Democrat Edward Pou probably made the implicit fears of some of his colleagues explicit when he warned that if a Prohibition amendment could pass, then so might an amendment "to prescribe the qualification of voters in all the...states of the union".

Aside from Pou, South Carolina's Frederick Dominick and North Carolina's John Small also opposed the Eighteenth. So did three Kentuckians: Arthur Rouse, James Cantrill, and Joseph Sherley. I imagine alcohol was a larger part of the culture and economy of Kentucky than in other Southern and border states (after seeing the map, a friend pointed out that one of their districts included Bourbon County). Their districts were also relatively urbanized: Sherley represented Louisville, Cantrill's district included Lexington, and Rouse's district was adjacent to Cincinnati and its significant German-American population (see below).

If I remember V.O. Key's "Southern Politics" correctly, the divide in Southern states over "moral issues" was often between their more urban, coastal, and commercial areas (which tended to support laxer policies and often had larger African-American percentages) and their whiter, more rural areas (which tended to support more restrictive policies).

The divisions in Alabama and Louisiana might fit that pattern here, although they only cover some of Alabama's "black belt". Interestingly, the specific example that I remember from Key is Mississippi, whose House delegation was unanimously "dry".

German-American Regions:

I've read historians who point out connections between the Prohibition movement and nativism--alcohol being a larger part of the cultures and even religious ceremonies of Irish, Italian, and German immigrants than of the (official) culture of "old stock" Protestants and so forth. And of course, urban "machines" surely liked their taverns and saloons, although I'm sure many of them learned to love Prohibition even more.

Here is Wikipedia on where German-Americans were concentrated. Compare with the vote map:

The cities of Milwaukee, Cincinnati, St. Louis, Chicago, New York, and Baltimore were favored destinations of German immigrants. Also, the Northern Kentucky area was a favored destination. By 1900, the populations of the cities of Cleveland, Milwaukee, Hoboken, and Cincinnati were all more than 40% German American. Dubuque and Davenport, Iowa had even larger proportions, as did Omaha, Nebraska, where the proportion of German Americans was 57% in 1910. In many other Northern cities, such as Fort Wayne, Indiana, German Americans were at least 30% of the population.[24][36] Many concentrations acquired distinctive names suggesting their heritage, such as the "Over-the-Rhine" district in Cincinnati and "German Village" in Columbus, Ohio.[37]

A favorite destination was Milwaukee, known as "the German Athens". Radical Germans trained in politics in the old country dominated the city's Socialists. Skilled workers dominated many crafts, while entrepreneurs created the brewing industry; the most famous brands included Pabst, Schlitz, Miller, and Blatz.[38]

Whereas half of German immigrants settled in cities, the other half established farms in the Midwest. From Ohio to the Plains states, a heavy presence persists in rural areas into the 21st century.[19][39] Few Germans settled in the Deep South, apart from some in New Orleans.[40]

To back that up, here is a Stanford visualization of German-language newspapers in 1917:

And here is a lovely map of the German-American population of about 1872 from that Wikipedia page:

There isn't a perfect correspondence, but there's enough to be interesting. Along with some of the big cities we've already discussed, the eastern border of Wisconsin (up from Milwaukee), the Western border of Ohio (up from Cincinnati), the St. Louis area, Northern Kentucky, Erie, Pennsylvania--all seem to have had high percentages of German-Americans, and all had Representatives voting against Prohibition. (The votes in Rhode Island's three districts seem to match pretty well with the 1872 map.)

The sole Iowa vote against Prohibition came from Harry Hull, whose district included Davenport's Scott county, and who succeeded another anti-Prohibition Congressman, the former Davenport Mayor and "archetypal German-American politician" Henry Vollmer.

However, there are exceptions: Omaha was heavily German-American, and the Representative of the Omaha district, Charles Lobeck, was himself German-American. Lobeck voted for the Eighteenth anyway. The entire Indiana delegation voted for Prohibition as well.

The West:

Representatives from the West voted heavily "dry", and much of the West was dry before the vote on the Eighteenth. California wasn't dry, but did have this depressing law:

Only a few Western Representatives opposed the Eighteenth amendment, including three urbanites (Portland's Clifton McArthur and the San Francisco Republicans Julius Kahn and John Nolan).

California Democrat Clarence Lea had a sound parochial reason for his vote against total Prohibition: He represented California's wine country. In fact, citing "conditions that affect my district", he proposed an amendment on the day of the vote "exempting light wines and beers containing not more than 3 per cent. of alcohol".

The other Westerners opposing Prohibition were the Central Valley Democrat, Denver Church, and Nevada's Edwin Roberts. (Nevada remained mostly "wet" before the vote.) Roberts was eventually elected the Mayor of Reno, where he remained defiantly anti-Prohibition, once claiming in a speech "that the only way to deal with bootlegging was to 'place a barrel of whiskey with a dipper in it on every corner.'"

One notable Westerner voting for the Eighteenth was Montana At-Large Republican Jeannette Rankin. (Montana also had an At-Large Democrat voting "dry", John Evans, but I decided to map Rankin for her historical importance.)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)